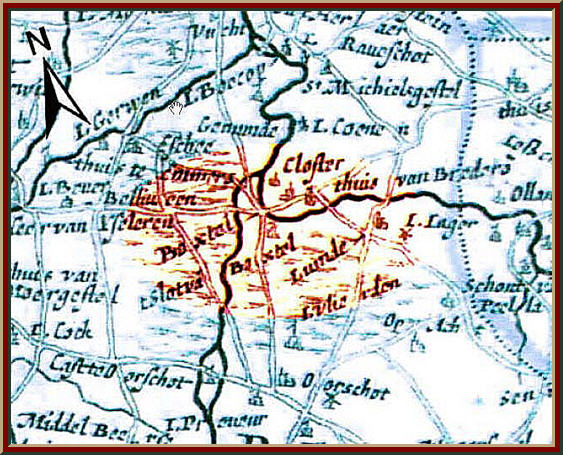

Richard Sharpe began his fighting career in a short, foggy action at Boxtel in Flanders while a common soldier in the King's 33rd Foot under

the command of a youthful Lieutenant Colonel, Sir Arthur Wellesley. The two men's careers would closely parallel each other until the final conflict with Napoleon at Waterloo. He didn't see much of Flanders as he wasn't there long and soon found himself on the battlefields of the Third Maratha War on the northern plains of India. He would experience the slaughter at Seringapatam, Aurungabad, Assaye, Argaum and Gawilghur and return to England via the Battle of Trafalgar as a new Second Lieutenant in the 95th Rifles. Adventure in Denmark would follow before he embarked on the longest campaign of his soldiering days, the Penninsular War.

The Peninsular War was probably the worst mistake Napoleon Bonaparte made during his lengthy reign over France - the attempted subjugation of Portugal in a bid to tighten his trade blockade of Britain. To get at Portugal, Bonaparte had to trick his ally Spain into allowing a French army under General Jean-Andoche Junot to move through its territory. On 1 December 1807, the French captured Lisbon, just missing the royal family who fled to Brazil the day before Junot arrived.

Just three months later, Marshal Joachim Murat took a huge army into Spain on the pretext of restoring order - the king, Charles IV, was quarreling with his son and soon had the entire family taken to France for protection. He later abdicated in favor of his son who became Ferdinand VII who was a hostage under the control of the French.

Bonaparte made the major error of appointing his brother Joseph as the new King of Spain, rubber-stamped by the large party of French-loving reformists, a move that sent the peasantry and the Catholic Church into a rebellious frenzy. Within two months there were open uprisings against Joseph and the conflict descended into one of the most brutal periods of warfare ever seen in Europe. The Spanish artist Goya sketched a series of ink images, Disasters of War, that depict much of the barbarity reached during the campaign.

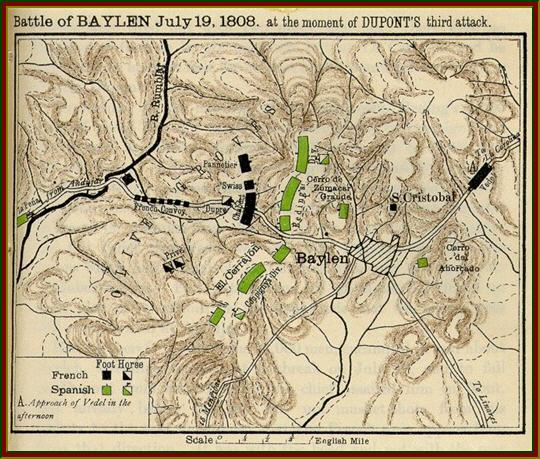

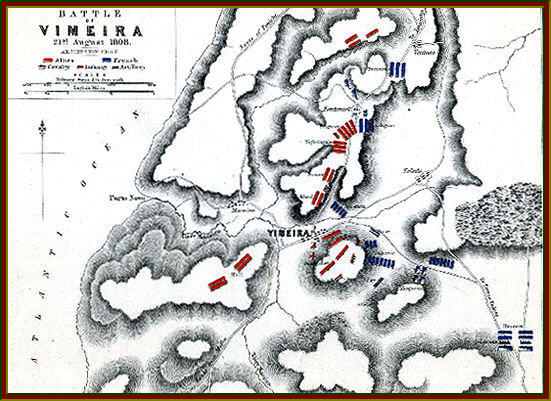

Despite its shockingly ineffective regular army, the war began well for Spain with the French being forced into a lengthy siege at Saragossa and the French army, under the luckless General Pierre Dupont was forced to surrender at Bailen. The reverses in Spain cut Junot off from any support he might have anticipated, but he felt strong enough to defeat a British army that landed in Portugal on 1 August, 1808. Unfortunately, for Junot and France, the British were led by the "Boy" Wellesley, whose military prowess was fostered in India and was therefore an unrecognized commodity in Europe.

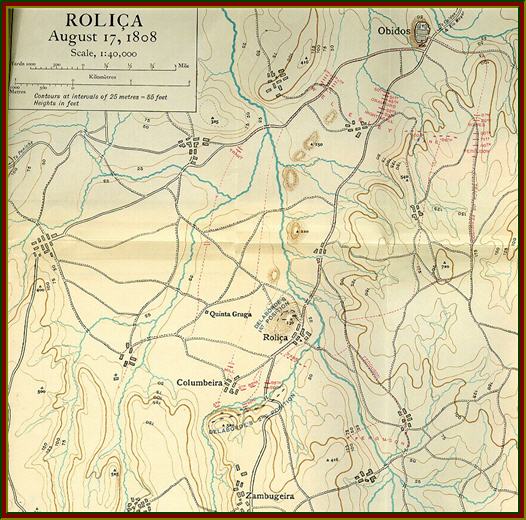

Wellesley beat General Delaborde at Rolica on 17 August and four days later took on a reinforced Junot at Vimiero. The battle ended in victory for the maligned "Sepoy General" Wellesley and with the French on their knees, British idiocy took over when two geriatric generals - Sir Harry "Betty" Burrard and Sir Hew "Dowager" Dalrymple - were placed in command of British forces. The pair negotiated the embarrassing Convention of Cintra with Junot that allowed the trapped French force to withdraw all troops, with all their equipment, on British ships back to France.

Wellesley, Burrard and Dalrymple were all brought before an inquiry where only Wellesley was acquitted of any wrong-doing. In the meantime, Sir John Moore took over the British army and, in expectation of major support from the Spanish, advanced deep into Spain. He was badly let down by the Spanish and found himself without support and up against no lesser opponent than Bonaparte himself.

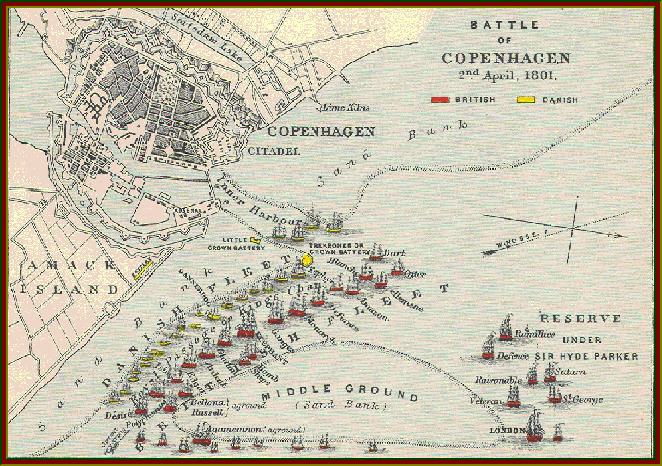

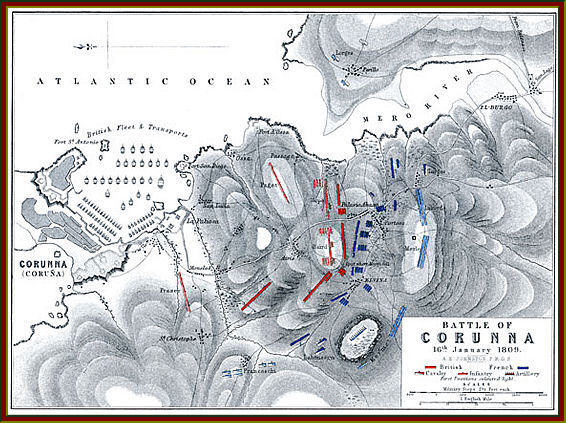

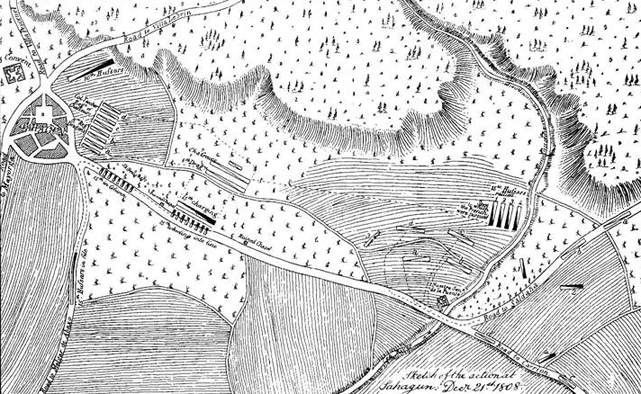

Fearful of being trapped between no less than three French armies, Moore turned his army around and began a horrendous retreat through winter-blasted mountains that tested the British army to its limits. When faced with destruction, however, the exhausted Redcoats turned on their attackers and saw them off. They won clashes at Sahagun, Benavente and Cacobelos. The city of Corunna was the safehaven for Moore as the Royal Navy was waiting to evacuate his army. While Moore marched for Corunna, General Black Bob Craufurd took the Light Division and the 2 Bn/95th Rifles on towards the port of Vigo, withdrawing in good order under the circumstances, which drew off a good portion of French cavalry from the pursuit of Moore's force. With Marshal Soult now at his heels, Moore arrived at Corunna and organised a defensive perimeter to hold the French at bay while his men embarked.

Corunna was a victory for Britain, but Moore died during the battle, opening the way for the return of Wellesley as commander. With the extremely capable Sir William Beresford retraining and reorganising the Portuguese army, Wellesley at last had allies he could trust and caught Marshal Nicholas Soult unprepared when he crossed the Douro River at Oporto and seized the military initiative.

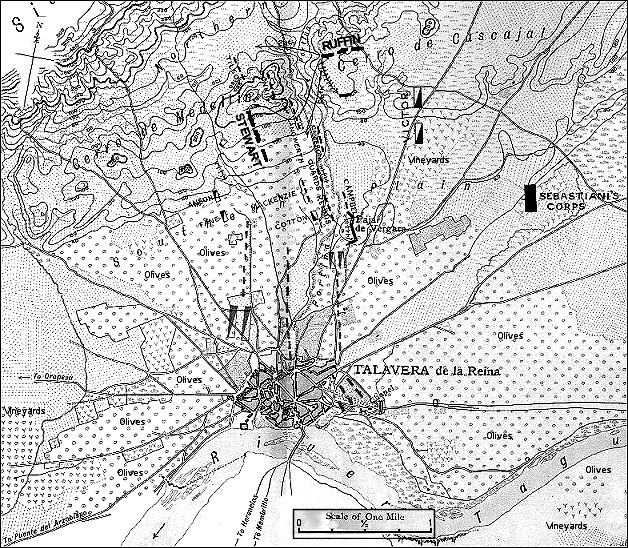

Moving into Spain, Wellesley was attacked by the French at Talavera, where the duplicitous Spanish general Gregorio de la Cuesta did nothing as the British fought tooth and nail to defeat Marshal Victor and Joseph Bonaparte's army. Deciding against trusting the Spaniards again, the newly-made Lord Wellington of Talavera was forced to fall back into Portugal where he waited for the next opportunity to take on the French.

By 1810, Wellesley had covertly constructed the impenetrable series of defensive fortifications, the Lines of Torres Vedras, which completely cut off Lisbon from attack and stymied the new-appointed Marshal Andre Massena's forces who had high expectations of an easy victory over the Anglo-Portuguese. Massena's invasion of Portugal earned him a bloody nose at Bussaco and before he had time to reorganise for another attempt at Wellington, the British commander had withdrawn behind the defensive perimeter at Torres Vedras. The French Marshal made some vain attempts to get through the lines and then sat obstinately outside them waiting for another chance to be at the British.

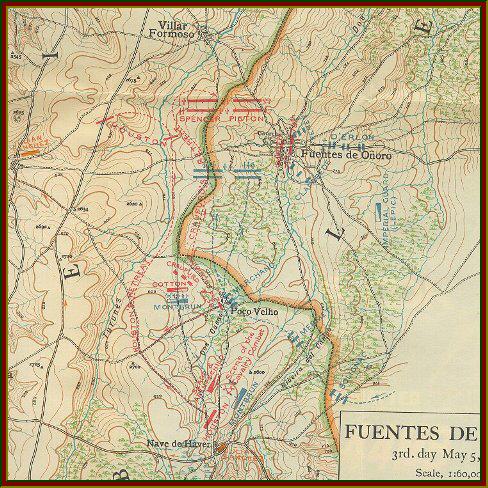

Wellington had other ideas and just waited for hunger, the lands having been cleared of foodstuffs and much of the forage-laden lowlands inundated, to take effect. It took the entire winter for Massena to accept defeat and he was finally forced to march his starving army towards more fruitful territory. The British won a further battle at Barrossa as Massena retreated followed by an encounter at Fuentes de Onoro which ended indecisively, with both British and French forces near equally bloodied.

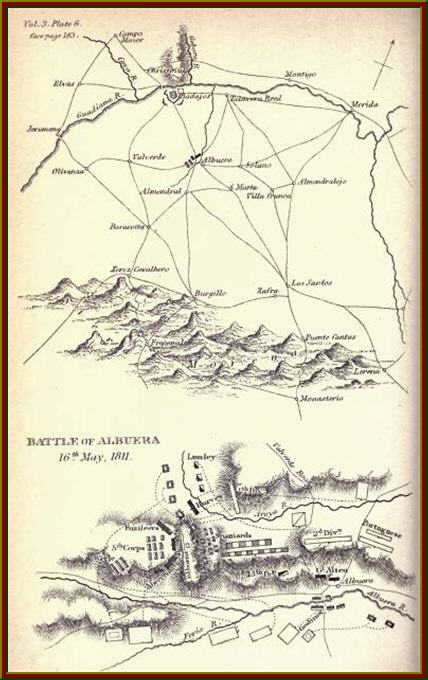

In 1811, one of the most bloody encounters on the Peninsula occurred when Soult moved to relieve the siege of Badajoz, a fortress guarding the Portuguese-Spanish border. Marching towards the city, he attacked a blocking force under Beresford at Albuera. The battle was up-close and nasty with the two lines of troops separated by a mere 20 paces. In the end it was the obstinacy of the British that won them the battle. Soult later remarked that the Redcoats just didn't understand when they were beaten.

While Wellington's army was the master of the countryside, the French still garrisoned the key fortresses of Badajoz and Ciudad Rodrigo. The mighty towns stood as gatekeepers into Spain and the British leader knew he had to capture them before taking on the French in Spain. As careful of his mens' lives as he was, Wellington lost caution when storming the fortresses and both Ciudad Rodrigo (19 January) and Badajoz (19 April) were extremely bloody affairs that cost thousands of British lives and then thousands more French and Spanish lives inside the cities as the Redcoats were given free reign. The sacking of both fortress cities brought little honour to Britain.

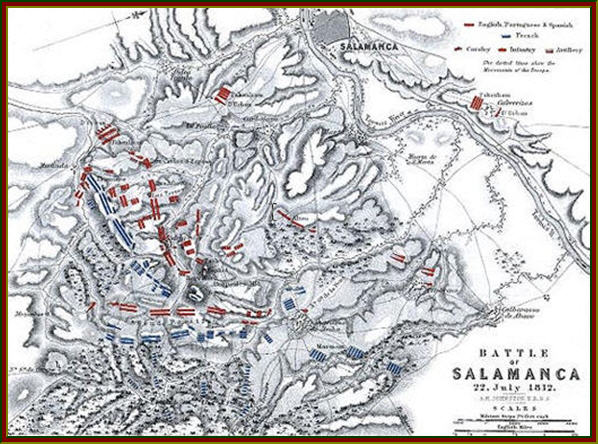

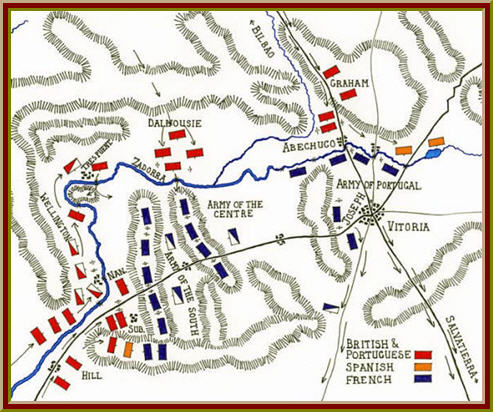

Moving quickly into Spain, Wellington found himself up against a new French commander, Marshal Auguste Marmont. He dealt with him the same way as the others and defeated him soundly at Salamanca, shortly after freeing Madrid. Unable to capture the fortress at Burgos, the British had to make another retreat to safety in Portugal as another fierce Penninsula Winter set in, but not before the back of French occupation was broken at the battle of Vitoria where King Joseph not only lost his crown and his royal piss pot, but also millions of pounds worth of treasure.

Soult now took over command of a unified French force and conducted a brilliant series of rearguard battles through the Pyrenees.

By early Spring, Wellington forced his way through, bursting through the mountain passes and overran the border fortresses, defeating Soult at Orthez and then, finally, at Toulouse. The Peninsular War was finally over and Sharpe took a well-earned rest in Normandy, until that is, Napoleon Bonaparte decided he didn't particularly care for his forced exile on Elba. Sharpe and Harper marched off to war once again for the Hundred Days War that finally saw the end of Napoleon's vision of a French Republican Empire in Europe.

With 21 books in the Sharpe series, Bernard Cornwell has built a number of them

around one or more of the actions that the British Army was involved in. He

has said in interviews that he isn't quite finished with Richard Sharpe yet.

As such, many of the actions found in this directory have never been included

in any of the current Sharpe novels. Will he witness any of them in future volumes?

Only Bernard Cornwell knows for certain, and he's not telling.

|

Wellesley ordered his army's offensive deployment to commence against Scindia on 6 Aug, 1803. Siege planning had been completed and Wellesley and his force arrived at Ahmadnagar on 8 Aug, just as a letter requesting surrender was delivered to the fort. The proposal was refused as was a subsequent offer of protection to the pettah outside the fortress, if it were to accept occupation.

Wellesley set his plan in motion with an initial attack on the pettah, to cover the second stage of the attach, that on the actual fort itself. The story of the brief struggle for the pettah is often accompanied by a quotation attributed to Maratha General Gokale: "These English are a strange people, and their General a wonderful man: they came here in the morning, looked at the Pettah wall, walked over it, killed all the garrison and returned to breakfast! What can withstand them?"

Although the facts are disputed, the fort was taken by escalade, even after it was discovered that there was no firestep or rampart inside the pettah wall and once inside, British soldiers had a straight drop down the other side. Artillery fire support was required to support the assault. Wellesley finally took the fort and city with a loss of nearly a fifth of his force after tough urban hand-to-hand fighting. After sacking the city and garrisoning the fort with loyal troops, Wellesley crossed the Godavary River and headed north towards Auringabad, but not before restoring the damaged walls and building a glacis to fortify the existing defenses.

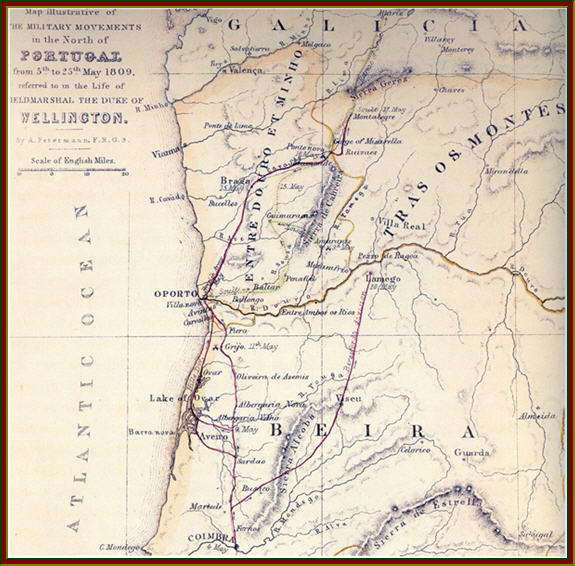

The combat of Albergaria Nova of 10 May 1809 was the result of an unsuccessful British attempt to trap the advance guard of Marshal Soult's army at Oporto at the start of Sir Arthur Wellesley's campaign in Northern Portugal of 1809.

Having occupied Oporto on 29 March 1809, Soult had posted Franceschi's cavalry division and Mermet's infantry divison between Oporto and the River Vouga thirty miles to the south. By early May those forces were strung out along the main road from Oporto to Coimbra. An advance guard of 1,200 cavalry, 700 infantry and one light gun battery was placed at Albergaria Nova, three miles north of the Vouga. Mermet's 3,500 strong division was split between Feira, fifteen miles to the north (4 battalions of the 31st Léger) and Grijon (7 battalions), five miles further north.

Wellesley hoped to surprise Franceschi's advanced guard and trap them between two forces. The main British force, five infantry brigades and the cavalry, would make a frontal assault on the French position, while Hill's and Cameron's brigades were to sail up the coast to Ovar, and then march inland to block Franceschi's retreat.

The plan failed for two reasons. For it to success, Wellesley had to attack the French before they realised he was close, but Soult had been received advance warning of the British attack from a very unexpected source on 8 May. Napoleon was not universally popular in the French Army, for a small core of officers believed that he had betrayed the revolution. When Wellesley arrived in Portugal he found that negotiations had been going on between his predecessor and a Captain Argenton. Wellesley met the French plotter, but was not impressed and had no interest in supporting his plans. Argenton returned to his lines, where he was arrested. On 8 May he was interrogated by Soult, and in an attempt to convince him to chance sides warned him that Wellesley was on his way. As a result of this when the British advance guard found Franceschi's force on 10 May there was no longer any chance of surprising them.

The second reason for the failure of Wellesley's plan was that it required a night march across unfamiliar country. The plan was for five squadrons of cavalry under General Cotton and the infantry brigades of Murray and Richard Stewart to attack together, drive in the French pickets and attack Franceschi's main force before they could prepare for battle. If they tried to retreat, Hill and Cameron would be blocking the road north.

Cotton, Murray and Richard Stewart all found that the night march took longer than expected. Cotton's cavalry finally attacked the French pickets at 5 am, but then discovered the rest of Franceschi's force drawn up in line of battle behind Albergaria Nova. Cotton was outnumbered nearly two-to-one, and decided not to risk a clash with the French until the infantry arrived. That wasted much of the morning, for the first three battalions of infantry were some hours behind Cotton's infantry. When they did finally arrive, Franceschi abandoned his position and retreated back to Grijon to join with Mermet. The only real fighting of the entire day followed, as the British 16th Light Dragoons attacked the French 1st Hussars, who had been left as a rearguard, and forced them to retreat.

If things had gone to plan, the retreating French should have run into Hill's infantry blocking the road north, but their amphibious flanking manoeuvre had fizzled out during the morning. They had reached Ovar according to plan, but then had discovered that there was a force of French infantry close by at Feire, and no sign of the British advancing from the south. Hill decided to wait in Ovar while Cameron's men were shipped up the coast. At noon, three battalions of French infantry arrived from Feire. Hill himself only had three battalions and a company of the rifles, and so was unable to make any progress. The situation only changed when Franceschi's men began to stream past, with the British cavalry in pursuit. At that point Hill attacked the skirmishes facing him at Ovar and forced them into a retreat.

At the end of the day the French advance guard had taken up a new position at Grijon, where on 11 May they would fight a more serious rearguard action.

In a brutal,

in-your-face battle where pure courage won the day for the British, a force

under Marshal Beresford had moved south away from Badajoz to fend off Marshal

Soult's attempt to relieve the first siege of that frontier fortress.

In a brutal,

in-your-face battle where pure courage won the day for the British, a force

under Marshal Beresford had moved south away from Badajoz to fend off Marshal

Soult's attempt to relieve the first siege of that frontier fortress.

Taking up positions at Albuera with some 35,000 men, made up of British, Portuguese

and Spanish troops, Beresford readied himself for Soult's 24,000 troops. In

a superb flanking manouevre, the French marshal attacked the Allies right wing,

brushing aside Spanish units and got ready to roll up the defenders' line.

Many of General Joachim Blake's Spaniards fought bravely against great odds

and a British counterattack failed with massive casualties - the result of a

blinding downpour that hid the proximity of Polish lancers until it was too

late. One British brigade suffered 80% casualties.

A second French attack almost succeeded, due to General d'Espana's refusal to

reinforce the line and poor communication high in the British command. A decision

by General Lowry Cole to hit the French column on its flank turned the battle,

but it was still desperate times.

For much of the firefight British and French troops were within 20 paces of

each other. After four hours of bitter fighting the French broke before a British

charge and the day was won. Marshal Beresford was severely criticised for his

leadership during the battle, but was backed up by the Duke of Wellington.

Combat of Aldea de Ponte

27 September 1811

The combat of Aldea de Ponte of 27 September 1811 was a rearguard action fought during Wellington's retreat from Fuente Guinaldo to Alfayates in the aftermath of the combat of El Boden. In August-September 1811 Wellington had been blockading Ciudad Rodrigo, but in late September Marshal Marmont had raised the blockade at the head of an army 58,000 strong. Most unusually Wellington had left his army rather dangerously stretched to the south and west of Ciudad Rodrigo while Marmont approached, and on 25 September had nearly paid for that mistake when a strong French cavalry force had come close to cutting Wellington's 3rd Division in half close to El Boden.

After some hard fighting the 3rd Division had escaped, but Wellington was still not out of danger. He had prepared two strong positions where he would have been willing to fight a defensive battle, one at Fuente Guinaldo, south of Ciudad Rodrigo, and one at Alfayates (or Alfaiates), thirteen miles to the west, just across the Portuguese border.

At the end of 25 September Wellington had the 3rd and 4th Divisions with him at Fuente Guinaldo, along with Pack's Portuguese brigade and part of his cavalry, giving him a total of 15,000 men. The Light Division was close by to the east, although would not reach the camp until the afternoon of 26 September, but the 1st and 6th Divisions had been posted along the Azava (or Azaba) river, to the west of Ciudad Rodrigo, and it soon became clear that they would not be able to reach Fuente Guinaldo.

Although Marmont had made no use of his infantry on 25 September, by the end of the day he had 20,000 infantry facing Wellington, and by noon on 26 September the entire French army was concentrated to the north of Fuente Guinaldo. If Wellington had been able to concentrate his entire army at that position, then he would have been willing to risk a battle, but throughout 26 September he was in a very vulnerable position.

Luckily for Wellington, Marmont decided not to attack. His reasoning was entirely logical - the French believed that in the past Wellington had not been willing to risk a battle unless he had a strong army in a strong position (they habitually overestimated the amount of men Wellington had at his disposal during his battles) - and so if Wellington was happy to spend all day in his position at Fuente Guinaldo then he must have enough men to defend it.

That night both armies began to retreat, Wellington west to his next position at Alfayates, and Marmont back to Ciudad Rodrigo. When Marmont's rearguard reported that the British were on the move, he ordered his army to turn around and follow Wellington. The French pursuit was too distant and too weak to worry Wellington, and by the end of 27 September he was secure in his new position.

The only fighting came at Aldea da Ponte, a village to the north east of Alfayates where several roads met. This position was defended by the pickets of the 4th Division and Slade's dragoons. Although it was not part of his main position, Wellington decided to defend Aldea da Ponte against any minor attack, and only abandon it if the French attacked in force.

The first French troops to reach Aldea da Ponte were Wathier's cavalry. They were soon joined by Thiébault's infantry division. At this point the village was defended by the light companies of the Fusilier brigade. Thiébault decided to send the three battalions of the 34th Léger to capture the village. One battalion attacked the village, while the other two outflanked the position, and the light companies were forced to retreat.

Wellington responded by sending the entire Fusilier brigade, supported by a Portuguese regiment, to recapture the village. The French battalion in the village was forced to retreat, and fusiliers took possession of the village.

This position lasted only lasted until dusk. Thiébault had been joined by Montbrun's cavalry and Souham's division. This time it was Souham who attacked the village, and once again the British were forced to retreat. With darkness approaching, and aware that the village was not part of his main defensive position, Wellington decided not to attempt to take it back.

The British and Portuguese suffered 100 casualties during this combat (71 in the Fusiliers, 13 in the Portuguese regiment and 10 in Slade's cavalry), while the French lost around 150 men.

Wellington was now in a very strong position, with both of his flanks protected by the River Coa and a front line said to be as strong as that defended at Bussaco. After examining this position on 28 September Marmont rather sensibly decided not to attack, and pulled back to Ciudad Rodrigo. On 1 October the French army was broken up and sent into its winter cantonments, and the danger to Wellington's army was over.

French Siege of Almeida

25 July-27 August 1810 (Sharpe's Gold)

The siege of Almeida of 25 July-27 August 1810 was a delaying action fought to slow down Marshal Masséna's invasion of Portugal in 1810, most famous for the dramatic explosion that ended the siege.

Almeida was the main Portuguese fortress on the northern invasion route from Spain, matching the Spanish fortress of Ciudad Rodrigo. In 1810 it was a well designed modern fortress, almost perfectly circular and protected by six bastions, a dry ditch and bombproof casements, was armed with 100 guns and was garrisoned by 4,000 infantry, 400 gunners and one squadron of cavalry, all under the command of William Cox, a colonel in the British army and a brigadier in the Portuguese. Wellington had made sure that the place was well stocked with food and ammunition. The hope was that Almeida would hold out for long enough to prevent the French from advancing into Portugal during the summer of 1810.

Despite its dramatic ending the siege actually satisfied this expectation. The last Allied troops in touch with Almeida, Craufurd's Light Division, were driven away on 25 July (Combat of the Coa), and Ney's 6th Corps began the blockade of Almeida. The siege itself did not begin for two more weeks, as it took some time for the heavy siege train to travel from Ciudad Rodrigo, and work did not start on the siege works until 15 August.

By the morning of 26 August the French had completed eleven batteries, and at six in the morning they opened fire. The town was soon on fire, and in three of the bastions the Portuguese gunners were pinned down, unable to return fire, but the walls were still intact.

That evening a chance event ended any realistic prospects of prolonging the siege. The main powder magazine was in the elderly castle of Almeida. At about seven in the evening the main door to the magazine was open and a powder convoy was leaving to resupply the guns on the southern walls. According to the only survivor of the disaster, a French shell landed in the castle courtyard and ignited a trail of powder that led from a leaking barrel back into the magazine. A second barrel, just inside the door exploded, and this blast ignited the main powder store. The massive explosion destroyed the castle, the cathedral and removed the roofs from all but five houses in the town. Over 500 members of the garrison were killed, amongst them half of the gunners. Some of the stones were flown so far that they killed men in the French trenches.

The defence was effectively over. The only way to move around the town was on the ramparts, for the interior was completely blocked with ruins. Only 39 barrels of powder and a few hundred rounds that had already been moved to the walls survived the explosion, just enough for one day's fighting but no more.

Cox was determined to fight on, at least for long enough to give Wellington a chance to rescue the garrison. This was always going to be a forlorn hope, for Wellington had never had any intention to attack Masséna's army on the Portuguese border - the risk was simply too great. Unsurprisingly the explosion had totally demoralised the Portuguese garrison of the town, especially some of the officers. Although Cox attempted to bluff the French, holding a conference with French officers in a closed casement to hide the damage, some of the Portuguese officers told the French exactly what had happened. When Cox sent Major Barreiros of the Artillery to negotiate with the French, he changes sides and told Masséna that there would be no further resistance.

Reassured by this, Masséna turned down all of Cox's requests for delays, and at seven in the evening of 27 August renewed the bombardment. A delegation of Portuguese officers then informed Cox that if he did not surrender, they would open the gates. Cox had no choice but to capitulate. On the next morning the 4,000 survivors of the garrison marched out of the town. Under the terms of the surrender Masséna had agreed to allow the militia to go home on parole while the regulars were to be taken back to France as prisoners. Masséna broke this agreement with breathtaking speed, and instead attempted to recruit the Portuguese prisoners into his own army.

Most of the surviving regulars and 600 of the militia immediately enlisted with the French, giving Wellington a real scare. If he could not rely on the Portuguese, then his entire plan of campaign was in danger. He need not have worried. Over the next few days most of the three battalions Masséna thought he had recruited absconded, often in large parties, and made their way back to the Allied lines. At first Wellington was worried about employing officers who had theoretically broken their parole, but the Portuguese government had no such concerns, and as Masséna had broken his word first Wellington's concerns were short-lived.

British Siege of Almeida

April-10 May 1811

The siege of Almeida of April-10 May 1811 saw Wellington's army capture the last French stronghold left in Portugal after Marshal Masséna's retreat from the Lines of Torres Vedras. Almeida had been captured early in Masséna's invasion of Portugal in 1810, and the area had been occupied by General Drouet's 9th Corps. As Masséna retreated past Almeida towards Ciudad Rodrigo, Drouet was forced to abandon his own advanced position. Not knowing this, on 7 April Wellington sent Trant's militia and Slade's cavalry brigade towards Almeida, in an attempt to force Drouet to retreat. One of Drouet's two divisions had already left, but close to Almeida they found Claparéde's division, and a brief skirmish followed which saw the French retreat towards the Agueda River in battalion squares.

Wellington did not have a siege train with his army, and so he had to settle down to starve out the small French garrison of Almeida. Most of his army was posted between Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo, while the 6th Division and Pack's Portuguese brigade carried out the actual blockade. The French garrison was tiny - General Brennier had just over 1,300 men in the town, formed from one battalion of the 82nd Line and a provisional battalion of artillery and sappers. They had enough food to last a month, despite Masséna's men having taken 200,000 rations from the town as they passed.

The only way Brennier could hope to hold Almeida was if Masséna successfully broke the British blockade. At first Wellington dismissed this possibility, believing that the French Army of Portugal had been too badly disordered during its retreat to make any serious move forwards, but he was mistaken. Masséna was determined to retain possession of the fortress, and by the end of April had gathered together a strong relief force. This army advanced west from Ciudad Rodrigo, before being defeated by Wellington at Fuentes de Oñoro (3-5 May 1811).

After this defeat, Masséna abandoned any hope of relieving Almeida and instead decided to order Brennier to break out from the town. Three volunteers attempted to take this order into the town, and although two were caught and executed as spies, the third managed to get into the town. Brennier was ordered to break out to the north, where the Allied lines appeared to be thinnest. On the night of 7 May Brennier fired three heavy salvoes at five minute intervals to signal that he had received the order and on the following day Masséna began his retreat.

Even during the battle Almeida had still been blockaded by Pack's Portuguese brigade and the 2nd Regiment from the 6th Division, but once it was clear that Masséna was not going to attack again Wellington posted three brigades outside the town. If these men had been keeping a close watch on the town then the breakout would have been impossible, but General Campbell posted his men too far from the walls, and then failed to post pickets close to the walls.

During 8-9 May Brennier planted mines in the defences of Almeida, and spiked his guns. At 11.30pm on the night of 10 May he made his move. Forming his men into two columns, Brennier struck the Allied lines at the junction between the 1st Portuguese Regiment of Pack's Brigade and the 2nd Queen's Regiment of Burne's division, and easily broke through the Allied cordon. Five minutes later the mines in Almeida exploded, destroying much of the eastern and northern fortifications, and rendering the town useless to Wellington for some time. While the Allied troops outside Almeida attempted to discover what was going on, Brennier's men made their way towards the crucial bridge at Barba del Puerco.

Earlier in the day Wellington had decided to extend his lines to include this bridge, and had ordered General Erskine to move the 4th Regiment of the 4th Division to guard the bridge. It appears that Erskine failed to pass on this order until late in the day, and so the bridge was unguarded. The 4th Regiment did eventually catch up with Brennier while the French were crossing the bridge, as did the 36th Regiment, and the French suffered heavy casualties attempting to reach the bridge, but 940 of Brennier's 1,300 men made it to safety. Brennier himself was promoted to general of division for his achievement. On the British side Colonal Bevan of the 4th Regiment was blamed for the failure to block the bridge, and committed suicide rather than face a court of inquiry. Almeida itself was now useless to the Allies, although it was also denied to the French, who now had nothing to show for their massive invasion of Portugal in 1810.

Passage of the Alva River

17-18 March 1811

The passage of the Alva River of 17-18 March 1811 was a nearly bloodless success for Wellington's army during the French retreat from Portugal in the spring of 1811. On 16 March the French had abandoned their position on the Ceira River at Foz de Arouce, and retreated towards the Alva. Once there they discovered that the bridge at Ponte de Murcella had been destroyed by the Portuguese and were forced to spend the rest of the day repairing it, all the time expecting Wellington's advance guards to appear.

In fact Wellington had chosen to spend 16 March resting, partly in order to give a supply convoy time to reach his army. This gave Masséna enough time to get his army across the Alva, and to take up strong defensive positions on the north bank. The 2nd Corps was sent east, to defend the ford at Sarzedo, placing a detachment at Arganil on the south bank of the river. The 6th and 8th Corps remained around Ponte de Murcella, guarding the fords across the river.

The line of the Alva was a strong defensive position. During Masséna's advance into Portugal in 1810 Wellington had intended to defend, but to his surprise the French had chosen a more northerly road, crossing the ridge at Bussaco.

Now he was faced with the same defensive position, Wellington had no intention of launching a frontal assault against the strong French positions. Instead, the 1st, 3rd and 5th Divisions and the Portuguese brigades were all sent along the mountain road from Furcado to Arganil, while only two divisions were sent towards Ponte de Murcella. These last two divisions remained hidden from Ney, who could only see cavalry on the southern bank of the Alva.

During the afternoon of 17 March the main British column reached Arganil, driving out the detachment from Reynier's 2nd Corps. At this point no infantry had been seen at Ponte de Murcella, and Masséna was convinced that the British intended to either attack at Sarzedo, or to move even further east, cross the river beyond the French left, and attempt to block their line of retreat. Accordingly he ordered Junot's 8th Corps to leave its camps on the French right and move to Galiges, to the east of Sarzedo, to extend the French left.

Wellington's plan was actually rather less ambitious than Masséna believed. On the morning of 18 March the Guard's Brigade of the 1st Division left the road from Furcado to Arganil, and forced their way across the Alva at Pombeiro, between Ney's position at Ponte de Murcella and the rest of the French army. Realizing that he was in real danger of being trapped between the two wings of Wellington's army, Ney abandoned his position with great speed, and managed to elude Wellington's trap. Despite this, the British and Portuguese had forced the French out of a potentially very strong position with very little lose. The French were forced into a lengthy night march which saw the British capture 600 prisoners.

The Battle of Argaum took place on November 28, 1803, between the British under

the command of General Arthur Wellesley and the forces of The Rajah of Berar

under Scindia of Gwalior. Three of Wellesley's battalions, which had previously

fought well, on this occasion broke and fled, and the situation was at one time

very serious. Wellesley, however, succeeded in rallying them, and in the end

defeated the Marathas, with the loss of all their guns and baggage. The British

lost 346 killed or wounded.

The Rajah of Berar was a leader in the Maratha Empire, also known as the Maratha

Confederacy durind the Second Anglo-Maratha War. The Sindhia, also spelled Scindia, Sindia, or Shinde are a prominent Maratha family in India.

The combat of Arzobispo of 8 August 1809 was a minor French victory late in the Talavera campaign, which saw them force their way across the River Tagus. After their success at Talavera, the British and Spanish had been forced to retreat by the unexpected arrival of three French corps from the north west of Spain under Marshal Soult. The British slipped across the Tagus at Arzobispo on 4 August, and despite some delays the Spanish followed on the night of 5-6 August.

The Allied armies then moved west along the south bank of the Tagus, heading for the main road into Estremadura, leaving a strong rearguard to protect the river crossing. In total the Spanish left 8,000 men to guard the bridge (5,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry), under the overall command of the Duke of Albuquerque. They had two crossing to protect - the bridge at Arzobispo and a nearby ford at Azutan. The bridge itself was strongly held, with a detachment of infantry defending the medieval towers in the middle of the bridge and gun emplacements covering the approaches to the bridge, but the Spanish somewhat overestimated the difficult of the ford.

After spending 7 August investing the river, Soult's men discovered that the deep channel in the river was close to the north bank, and after that the river was only two or three feet deep. Once the French cavalry was past this deep channel, it could fan out to attack any part of the opposite bank. Their chance of success was greatly increased by Albuquerque's deployment - most of his men were held back from the river, with only one cavalry regiment watching the ford, and two infantry battalions at the bridge.

Soult launched his attack at 1.30pm, during the siesta. He sent his entire force of 4,000 cavalry to attack across the ford, supported by one brigade of infantry. A second infantry brigade was to watch the bridge, but was only to attack once the French had crossed the ford. Caulaincourt's brigade of dragoons, 600 strong, led the attack, and quickly swept away the Spanish cavalry. The Spanish responded by sending one battalion of infantry from the bridge, but it failed to form square in time and was cut up by the French cavalry. Over the next half hour the French were able to pass the rest of their cavalry across the ford.

This was the signal for the start of the attack on the bridge. Despite their strong position, the Spanish defenders of the bridge could see that their line of retreat was about to be blocked, and so after firing a couple of volleys fled east, away from the rest of Albuquerque's force. Only now did the rest of the Spanish force come into action. While the remaining infantry formed up on a hill above the bridge, Albuquerque led his 2,500 cavalry in a desperate charge against the leading French cavalry. Having wasted a crucial half an hour while the French were crossing the ford, the Spanish attack was carried out before the cavalry had a chance to form up properly, and was quickly repulsed by the more organised French. Seeing the cavalry defeated, the infantry abandoned their position, and retreated across the hills to safety.

The Spanish cavalry suffered heavily in the battle at the ford, losing 800 killed and wounded and 600 prisoners, leaving only 1,100 of the original 2,500 men still with the colours. The French captured 16 Spanish guns at the bridge, and fourteen of the guns they had lost at Talavera. Despite their success, the French crossed the Tagus too late to have any chance of catching the main Allied army. An attempt to cross the river further west, at Almaraz, failed after Ney's men could not find the fords they had been sent to cross. The British and Spanish took up a strong defensive position around Almaraz. Even Soult realised that this position was too strong to be assaulted, and proposed invading Portugal from Ciudad Rodrigo, but King Joseph opposed this plan. Instead the armies that had threatened Wellington were dispersed to deal with other threats.

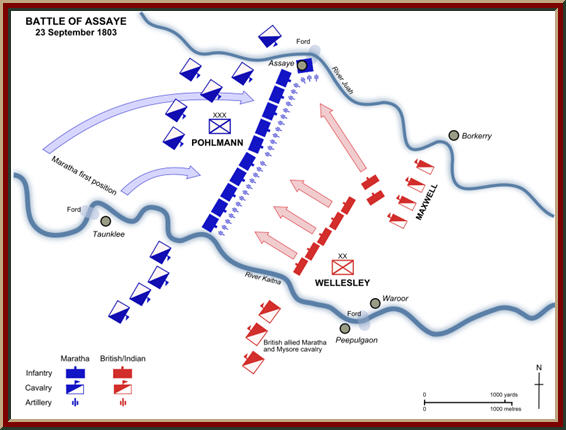

In charge of a British and sepoy army of some 13,500 men, General Arthur Wellesley took on a major Indian force at least three times the size of his own at Assaye.

The army of the princes of Scindia and Berar was drawn up between the Kaitna and Juah rivers - a position the leaders thought would force the British to attack them across the Kaitna.

Wellesley, however, found a nearby ford and crossed the river near the village of Assaye and moved against the enemy's left flank. The move was not without its dangers and only a strong counterattack by the British cavalry forced the elite Mahratta cavalry away. The well-trained Scindian infantry repositioned themselves quickly to cover the new threat and expert handling by a German soldier of fortune called Pohlman allowed the artillery to do likewise.

Against fierce resistance and with growing numbers of casualties, Wellesley led his men on, captured the enemy cannons and pushed the Scindian troops backwards.

The village of Assaye itself was a tough defensive nut to crack and, adding to Wellesley's difficulties, another Mahratta cavalry attack had to be seen off by the British cavalry. With the enemy horse dealt with, the British then turned their attention to the infantry and scattered several columns.

Wellesley now launched a major assault and broke the Scindians, who found themselves with their backs to the Juah river. By early evening, the princes were in retreat and left behind some 6000 casualties. The British had suffered 1600 killed and wounded.

|

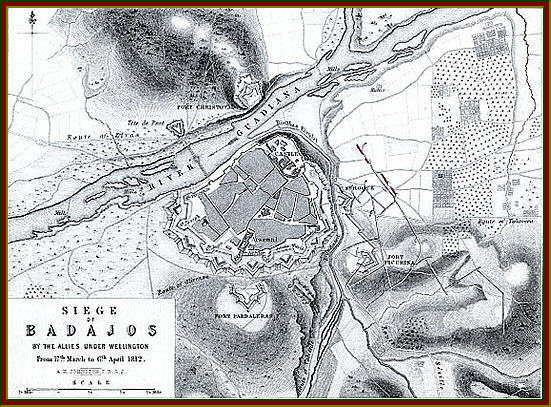

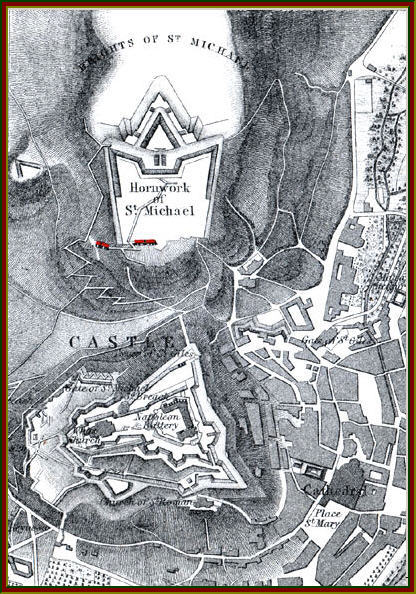

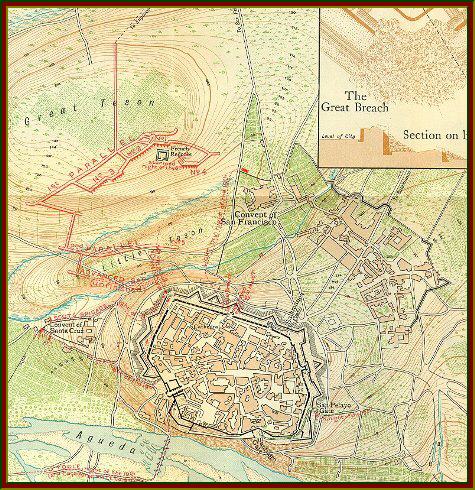

Badajoz

16 March, 1812 (Sharpe's Company)

More than 30,000 British troops blockaded the fortress at Badajoz, which commanded the southern route between Spain and Portugal. The siege commenced and by 6 April the 5000 defenders were steeling themselves to be attacked through three breaches.

The night assaults began bloodily against the formidable defences and more than 40 times did the redcoats throw themselves into attack. By midnight, two entries to the city had been forced and an hour later the defenders under General Phillipon holed up in Fort San Christobal and accepted terms later that day.

The city was sacked furiously by the hard-pressed British troops. French losses were almost 1500 men, while some 3500 British troops became casualties.

By 1808, thousands of French troops were present in Spain in support of Napoleon's invasion of Portugal. In April, Napoleon deposed the Spanish king, Charles IV, replacing him with his own brother Joseph. The Spanish army and people revolted (the Dos de Mayo Uprising) against the imposition of foreign rule.

With much of Spain in open revolt, General Dupont received an order to capture the city of Cádiz, where Admiral François Rosilly's fleet lay at anchor. Dupont's corps numbered 15,000 inexperienced and largely new recruits, grouped in three infantry divisions under Vedel, Barbour, and Gobert, and a cavalry division under General Fresii.

Dupont approached Cordoba in early June, forcing the Alcolea bridge, where Spanish militia under Colonel Echeveria attempted a stand on 6 June. The French entered Cordoba the next day and ransacked the town for four days. However, in the face of increasingly menacing mass uprisings across Andalusia, Dupont decided to withdraw to Sierra Morena, hoping for help from Madrid. General Gobert's division set out from Madrid with General Savary on 2 July, aiming to succour Dupont's beleaguered forces. However, only one brigade of his division ultimately reached Dupont, the rest being needed to hold the road north against the guerrillas.

The French retreated fitfully in the sweltering heat, impeded by 500 wagons of loot and 1,200 sick. General Vedel, likewise, withdrew from Toledo on 15 July, bringing 5,000 infantry, 450 cavalry and 10 cannons. On 18 July Dupont unwisely opted to linger at Andujar, setting up camp on the plains while Spanish troops marched to bar the road to the mountains. Under Dupont's orders, Vedel moved north to dislodge the militia holding the pass at Despeñaperros, opening an ominous gap between the French divisions. Garrisoning the pass with a battalion of infantry, Vedel turned to rejoin Dupont with the rest of his forces. But, Castaños seized the central position, placing 17,000 men and 12 guns between Dupont and Vedel.

After joining formations, Dupont's forces were divided into three groups: General Gobert's division in the village of La Carolina, General Vedel's division in Bailén and General Dupont and his forces occupied Andujar. Meanwhile, the Spanish Army, commanded by General Castaños, had more than 33,000 soldiers. He had under his command some regular regiments from Seville (also one from Switzerland) and formations of provincial militia and peasants. The size of Castaños' army far outweighed that of Dupont. When Dupont received information about Castaños's arrival, he ordered Vedel to join him in Andujar. After Vedel left Bailén, Spanish forces, commanded by General Reding, captured the town and successfully defended it against Corbert's brigade. During the attempt to recapture the town, General Corbert was killed and his brigade withdrew to La Carolina. After learning this, Dupont ordered Vedel to recapture the town; he succeeded, but afterwards he left the town to take up positions in Bailén.

Reding overtook the French along the banks of the Rumbla and crashed his division against the French rearguard, inflicting serious losses. The Swiss soldiers in Spanish employ advanced. Dupont called Vedel for help, but after the arrival of Castaños he decided to sign a truce. After learning this, Vedel withdrew to the mountains. Spanish commanders threatened to massacre the French soldiers if they didn't surrender.

On 22 July, the French II Corps of Observation, under Gironda, surrendered. Dupont and his soldiers were transported on English ships to Rochefort harbour because the Spanish junta in Seville didn't recognise the pact under which they were sent to Cadiz. Except for Dupont and his staff officers, they were placed on prison-ships converted for the purpose. Only a small number of the French soldiers survived to 1814.

Following their defeat, the remainder of the French army left Madrid under the command of Marshals Bessieres and Moncey. When they reached the Ebro river they set up new defensive positions. The Spanish victory at Bailén signalled to the armies of Europe that the French were not invincible - a fact that persuaded the Austrians to wage a new war against Napoleon.

Barba del Puerco

19-20 March 1810

The skirmish of Barba del Puerco of 19-20 March 1810 was a minor clash between part of Craufurd's line of outposts on the Portuguese border and part of the French army gathering in preparation for Massena's invasion of Portugal. In the spring of 1810 Craufurd's Light Division was watching the line of the Agueda River. Most of his infantry was pulled back from the river, but four companies of Beckwith's 95th Rifles were close to the river, watching the bridge of Barba del Puerco (north west of Ciudad Rodrigo). This was a strong position in a difficult pass, and Craufurd felt that the rifles would be able to hold off any force small enough to surprise them.

This was put to the test on the night of 19-20 March. Loison's division had taken up a position facing the northern stretch of the Agueda, with Ferey's brigade at San Felices. Ferey decided to make an attempt to capture the pass of Barba del Puerco by surprise. He gathered the six voltigeur companies of his brigade, and before dawn on 20 March surprised the sentries of the bridge, who were bayoneted before they could raise the alarm.

The French then began to climb up out of the river valley towards the village, but not without being detected. Craufurd's men took pride in the speed with which they could come to arms, and within ten minutes of the alarm being raised three companies of the 95th Rifles were in place to attack the French. Ferey's men were driven back across the bridge, losing two officers and forty five men during the fighting. Beckwith's rifles suffered four dead and ten wounded during the clash. For the next few days Craufurd was on alert, expecting a general French advance, but nothing happened until later April, when the French finally moved up towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

The combat of Barquilla of 10 July 1810 was one of the few failures for General Craufurd and the Light Division during Marshal Masséne's invasion of Portugal. Since the start of 1810 Craufurd had been watching the French along the line of the Agueda River. During the French siege of Ciudad Rodrigo (5 June-10 July 1810) he had been pushed back to Fort Concepcion, close to Almeida, but was still keeping an active watch on the French.

On 10 July Craufurd decided to attack some of the French foragers who were attempting to find food between the Azava and Dos Casas Rivers. Taking six squadrons of cavalry, six companies from the Rifles and the 43rd Foot, one battalion of Portuguese light infantry (the Caçadores) and two guns, he soon found a small party of French troops close to the village of Barquilla.

This French force was very badly outnumbered, and consisted of two troops of cavalry and 200 men from the 22nd Regiment of Junot's corps. As the British approached, the French began to retreat back towards their main lines. Craufurd ordered one squadron from the German Hussars and one from the 16th to attack the retreating French infantry.

The French responded by forming a small square. As nearly always happened, the cavalry were unable to break into this square, despite its small size. The first two squadrons failed to even attack the square, instead charging around its sides before heading off the chase the French cavalry. Craufurd then sent a squadron from the 14th Light Dragoons to attack the French square. This time the British cavalry closed with the French, but were repulsed by close-range musket fire. The colonel of the 14th and seven of his men were killed. Before Craufurd could bring up his next squadron, the French managed to escape into the next village. By now the first two cavalry squadrons were returning from their charge, and it is said that the British mistakenly believed them to be French cavalry.

Although Craufurd's men took 31 prisoners, they lost nine dead and twenty three wounded. Craufurd was much criticized for failing to bring his infantry up in time, and for allowing a smaller French force to escape from him, while the commander of the French square (Captain Gouache) was promoted and decorated for his skilful handling of affair.

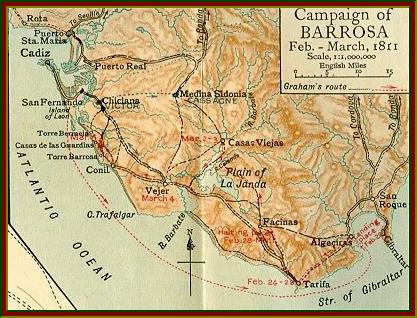

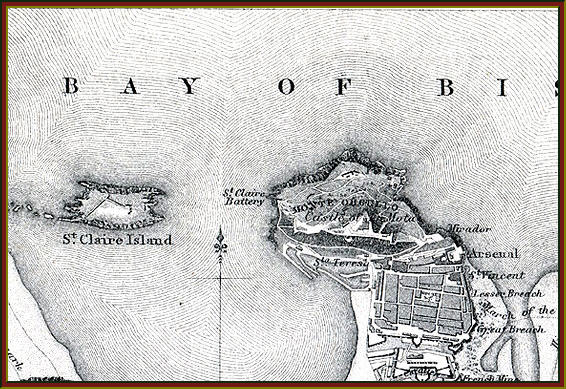

Barrosa

5 March, 1811 (Sharpe's Fury)

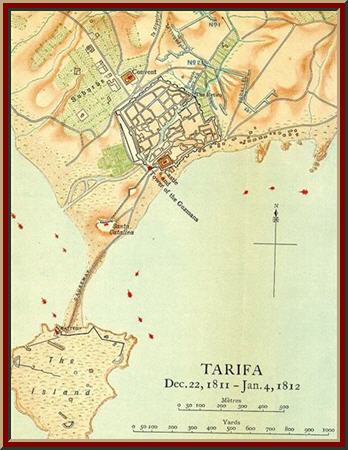

During his

blockade of the southern port of Cadiz, Marshal Victor heard of a combined British

and Spanish force moving to attack him in the rear. Splitting his force, he

moved the bulk - some 7000 men - against the enemy moving from the direction

of their landing point at Tarifa, between Cape Trafalgar and Gibraltar.

During his

blockade of the southern port of Cadiz, Marshal Victor heard of a combined British

and Spanish force moving to attack him in the rear. Splitting his force, he

moved the bulk - some 7000 men - against the enemy moving from the direction

of their landing point at Tarifa, between Cape Trafalgar and Gibraltar.

While they outnumbered Victor's troops by three-to-one, the Anglo-Spanish force

only had just over 5000 British troops under the command of Sir Thomas Graham.

The Spanish were led by the Count de la Pena and cooperation between the two

allies was poor to say the least. Their objective was actually to relieve the seige of Cadiz.

Despite having just completed 14 hours of marching, La Pena moved forward with the Spanish contingent on the 5th and successfully broke the French siege lines at Bermeja, forcing a French division under Gen. Villate back across the Almazna creek. At mid-day, the British contingent stationed on Barrosa Hill marched off to join La Pena, leaving behind several Spanish regiments and none other than Browne's Flank Battalion, containing the 2 companies of the 82nd. Half and hour later, with their artillery stuck in boggy ground, the French launched an infantry

assault and began a bloody exchange with Graham's men, a small blocking detachment, which was attacked by a good part of an entire French Division under Gen. Ruffin. The Spanish soldiers flew in a panic, making away with the baggage, while Browne's Battalion hastily beat to arms and retired in better order. Graham, now notified, ordered Brown to stand fast and fight, while the main British force marched to join them. This the battalion did, against fearful odds.

An account of the battle describes the action:

"Against the slender force Marshal Victor directed an overwhelming attack, and Browne retreated in good order. Then he sent for orders from Graham, who was then near Bermeja. 'Fight' was the laconic answer; and Graham, facing about himself, regained the open plain… when the view opened, he beheld Ruffin's brigade, flanked by the two grenadier battalions, near the summit on the one side, the Spanish rearguard and the baggage flying towards the sea on the other, the French cavalry following the fugitives in good order, Laval close upon his own left flank…Meanwhile Graham's Spartan order had sent Browne headlong upon Ruffin, and though nearly half his detachment went down under the first fire, he maintained the fight…a dreadful, and for some time doubtful, combat raged; but soon Ruffin and Chaudron Rousseau, who commanded the chosen grenadiers, fell, both mortally wounded; the English bore strongly onward, and their incessant slaughtering fire forced the French from the hill with the loss of 3 guns and many brave soldiers."[5]

After a short time of standing alone against at least 1,900 men and 5 guns, Browne's Battalion was joined by the rest of its brigade, under Gen. Dilkes. The British met with the French on the top of the hill and after a further bloody exchange of gunfire, the French broke and fled. Graham meanwhile was able to fight off an attack on the British left by Gen. Leval's division. The British then marched after the retreating French, who made haste back to the nearby town of Chiclana and so the battle ended. Soon after, Graham ordered his British contingent into Cadiz, the action having died down at sunset and Graham, fearing French reinforcements arriving, withdrew. Angered that La Pena had refused to join the battle Graham refused to take further commands from the Spanish general. With the allied army now broken up, the Spanish too absconded and Victor was shortly thereafter able re-commence the siege.

Casualties were high on both sides with the British losing some 1200 men, while

Victor suffered more than 2000.

The futile attempt cost the French just over 900 casualties and the British some 840. A major loss for the besieging army was when General Lord Andrew Hay was mortally wounded.

Despite knowing of the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte, the besieged governor of Bayonne, General Pierre Thouvenot, decided he would break out from the British encirclement.

On a pitch-black night, the general led 5000 men in a surprise attack against the British lines and threw the redcoat army into utter confusion. Quick-reacting reinforcements contained the threat and then forced Thouvenot's men back. Bayonne was eventually surrendered on 27 April.

As Sir John Moore's men pulled away from Napoleon Bonaparte's fast-approaching army, the French sent 600 cavalry under General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes to disrupt the British retreat. At Benavente a small French cavalry force was ambushed and defeated by the British and German cavalry. French General Lefebvre-Desnouettes crossed the river and impetuously attacked the British and German cavalry. The enemy at first gave way. They caught the enemy rearguard at the River Coa. General Stewart soon brought in more cavalry. The French continued advancing, but the courage of a small group of British cavalry earned enough time for Henry Paget (Lord Uxbridge) to organise a defence. Paget, accompanied by a hussar regiment ambushed them and pursued the surprised and retreating enemy back across the Coa

The British suffered some dozen casualties and British-German cavalry captured 70-100 prisoners, including Lefebvre-Desnouettes. Despite the moral-boosting success in this small combat, Moore's retreat towards the sea continued. Soult, meanwhile, maintained the pressure on the fleeing British corps.

The straggler's battle at Betanzos of 10 January 1809 was an incident late in Sir John Moore's retreat to Corunna in the winter of 1808-1809. After a long retreat the British had made a stand at Lugo, but the pursuing French army under Marshal Soult had refused the strong British position, and at midnight on 8-9 January the British had slipped away, heading towards the coast at Betanzos. Discipline soon began to collapse, and large numbers of men fell behind the rearguard. On the morning of 10 January most of the army had reached Betanzos, while the rearguard under General Paget took up a position on some low hills just outside the town. From there they were able to observe the French cavalry under Franceschi as they began to round up large numbers of the stragglers. About 500 British soldiers were captured on 10 January, and a similar number had been lost on the previous day.

The losses were kept down by a spontaneous fight back on the part of some of the stragglers. As the French cavalry approached a large concentration of British troops in the villages at the foot of the hills, the more able bodied soldiers grabbed their muskets, and managed to hold off this first French charge with a rolling fire. At this point William Newman, a sergeant in the 43rd Regiment, took command of this impromptu force. He then divided into two companies, and conducted a skilful fighting retreat down the road into Betanzos, with the two companies covering each others retreats. Despite several French cavalry charges, the party of stragglers was able to reach the British lines in safety, while another 500 men are reported to have taken advantage of the distraction to escape from the French. Newman was rewarded for his achievement with an ensign's commission in the 1st West India Regiment.

Part of the Flanders Campaign of 1793-94, the Battle of Boxtel was a minor incident during the Allied retreat from Belgium after the battle of Fleurus that is chiefly remembered for being the first time Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, came under fire in command of the British troops of the King's 33rd Foot. The allied expedition had planned to overthrow the French Revolutionaries by invading France from the north through Flanders in co-ordination with other similar attacks from different directions. These forces had initially been successful but had suffered a serious reverse outside Dunkirk and at Fleurus.

By 1794 the allies were retreating back northwards, pursued by an increasingly resurgent French army. In the aftermath of the Allied defeat at Fleurus the Austrians had begun to pull back east towards the line of the Rhine, abandoning any hope of recovering the Austrian Netherlands. This forced the British and Dutch to pull back towards the Netherlands, and by the end of August the Duke of York's British and German army was located between Hertogenbosch (Bois-le-Duc) and the Peel to the east (an area on the border of North Brabant and Limburg). The British line was protected by the River Aa, which runs south east from Hertogenbosch to the Peel, and the River Dommel, which runs south from 's Hertogenbosch to Boxtel and then turns south east to run alongside the Aa. In mid-September the French caught up with the Allied rearguard near the small town of Boxtel, on the Dommel river, and on the Kovering Moor, north of St. Oedenrode village, and south of Veghel.

General Pichegru, with the French Army of the North, had just advanced from Antwerp to Hoogstaeten, and had sent out a strong detachment to occupy Eindhoven. On 4 September Pichegru advanced north from Hoogstaeten as if he was about to threaten Breda, but on 10 September he turned east, and advanced towards the British outpost at Boxtel, which was defended by two battalions of Hessians. On 14 September the French captured Boxtel, defeating three German battalions from the Duke of York`s Allied army and taking the Hessians prisoner.

The next day, York sent a division commanded by Abercromby to recover the town. Abercromby was given ten infantry battalions and ten cavalry squadrons, with the infantry made up of the Guards Brigade and the 3rd Brigade. This second brigade contained four infantry battalions, amongst them Wellesley's 33rd Foot. As the senior colonel present, Wellesley commanded the brigade while John Sherbrooke, the second lieutenant colonel of the regiment, had command of the 33rd on the day.

As the British force advanced towards Boxtel, it became clear that they were in danger of running into Pichegru's main force and ran into an ambush. Abercromby decided to pull back to his starting point and was forced to retire in confusion, pursued by French cavalry. When two French infantry regiments turned to follow the British, the retreat threatened to turn into a rout, but the situation was saved by the 33rd Foot, who formed up into line and fired a series of disciplined volleys which drove off the French. The young Wellesley was not directly responsible for their good behaviour, but was given much of the credit. After this rearguard action the British returned to safety with the loss of only ninety men. The battle was a baptism of fire for Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Wellesley, future Duke of Wellington, who checked the French pursuit by close-range volley fire. The regiment lost 430 men dead, but only 6 of them killed by the French, the rest dying as a result of the weather and starvation).

In the aftermath of this failure the Duke of York realised that he could no longer hold his line of the Aa, and the British withdrew east to cross the Maas (Meuse) at Grave. They then took up a new position on the north bank of that river, with the Duke's headquarters at Wijceen. The French soon forced the British to give up this line as well, and at the start of October the Duke of York was forced to retreat across the Waal (a major branch of the Rhine). The British were able to continue their advance northwards and eventually reached the North Sea coast successfully, where they were withdrawn to Britain in 1795. The French pressed on to Amsterdam and overthrew the Dutch Republic and replaced it with a satellite state.

Burgos

19 September - 22 October, 1812, 10-12 June, 1813

The Duke of Wellington laid siege to Burgos twice, the first being a costly failure, while the second a quick victory.

The first attempt against the 2000 Frenchmen garrisoning the fortress was hampered by huge amounts of rain and a lack of British siege artillery. Progress was woefully slow and despite gaining footholds in Burgos, the British were never able to seriously threaten its security. The gathering of two French forces to relieve the defenders sparked a British withdrawal. The month-long siege had cost Wellington more than 2000 men, while the French lost only some 600.

Ten months later, a second move on Burgos captured the city within two days.

|

The action at the defile of Cacabellos, 3 January 1809, was a minor British victory during Sir John Moore's retreat to Corunna. It was fought between the British rearguard and the lead elements of Marshal Soult's pursuing army. The purpose of the British stand was to give Moore time to destroy the stores at his main supply depot at Villafranca, six miles to the west.

The British rearguard consisted of five battalions of the Reserve under the command of General Edward Paget, the 15th Hussars and a battery of horse-artillery. Most of this force was posted on the west bank of the river Cua, with one squadron of cavalry and half of the 95th Rifles on the east bank. The artillery, protected by the 28th, was placed on the slopes opposite the bridge over the river, with the remaining British troops hidden to either side.

The first French troops to reach the defile, at about one in the afternoon, were a cavalry brigade from Ney's corps (containing the 15th Chasseurs and the 3rd Hussars), under the command of General Colbert, and a division of dragoons under General Lahoussaye.

As the French approached, the 95th Rifles began to cross back over the bridge, while the squadron of British cavalry remained on the east bank to watch the French. Colbert observed this, and decided to attempt to force his way across the bridge with a cavalry charge. His first charge was a success - the British cavalry were forced to flee, reaching the bridge at the same time as the last of the rifles, causing chaos. The French took between 40 and 50 prisoners before the rest of the riflemen were able to escape.

Colbert was still on the east bank of the river, but from his position the only British troops in sight were the artillery and 28th. Accordingly he decided to try another cavalry charge. Forming his men into a column four wide, he led a charge across the bridge. Artillery fire destroyed the head of the column, but most of Colbert's cavalry made it across the bridge. Once there they came under a heavy cross fire from the 95th and 52nd regiments, posted north and south of the bridge. Colbert, and his aide-de-camp Latour-Maubourg were both killed, and after a few costly minutes the survivors retreated back across the bridge. Most of the 200 French casualties were suffered during this part of the battle.

Lahoussaye's dragoons then made a second attempt to force the British out of their position, wading across the river at a number of places, but the rocky terrain was ill-suited to cavalry, and they were forced to dismount and act as skirmishers, without success.

Finally, close to dusk, General Merle's infantry division arrived. After an hour of skirmishing, Merle formed a column and attempted to force his way across the bridge, but this left the French infantry dangerously exposed to the British artillery, and the attempt failed. As darkness fell the British rearguard was still in place, but that night they were withdrawn by Moore, and the retreat continued.

Both sides lost around 200 men in the fighting, which gave the British the time they needed to destroy their supply depot at Villafranca. The retreat to Corunna continued, and Moore's army came close to falling apart. In retrospect Moore has been criticised for the speed of the retreat, and his failure to take better advantage of strong defensive positions like the Cacabellos defile, although when he did offer battle at Lugo on 6-7 January, the French sensibly refused to take the bait.

Combat of Carpio

25 September 1811

The combat of Carpio of 25 September 1811 was a minor clash between Wellington's cavalry screen and part of a French army under Marmont that had just raised the blockade of Ciudad Rodrigo. Having raised the blockade, Marmont decided to carry out a strong cavalry reconnaissance to discover if Wellington was preparing for a siege. One of these columns, containing two cavalry brigades under the command of General Wathier, was sent west from Ciudad Rodrigo to investigate the line of the Azaba (or Azava) River. This brought them up against Wellington's left wing, where the 1st and 6th Divisions under General Graham were guarding the road to Almeida and the supply depot at Villa da Ponte, while Anson's brigade was providing a cavalry screen across the Carpio road (a village just to the east of the Azaba).

Wathier's advance forced Anson's men to abandon their picket line, and pull back behind the Azaba. Wathier then left six of his squadrons at Carpio, and crossed the river with the remaining eight. Graham responded by moving the light companies of Hulse's brigade to the edge of a line of trees just to the west of the river. Anson's cavalry - the 14th and 16th Light Dragoons) also drew back to the edge of the trees.

The woods made Wathier nervous and he decided to send four of his eight squadrons forward to investigate. When the first of these squadrons came close to the woods, it was charged by one squadron from the 14th Light Dragoons and forced back onto the other three. All four of the French squadrons then continued their advance. As they came close to the woods, the three British light companies opened fire, and before the French could recover the British cavalry charged again. This time the French cavalry turned and fled, and were chased back to the river. The French lost 11 dead and 37 captured during this skirmish, while the British only lost 11 wounded and one missing. Although only a minor clash, the combat of Carpio did confirm that the British had infantry west of Carpio, and helped to built up Marmont's picture of Wellington's rather scattered disposition.

Combat of Campo Mayor

25 March 1811

The combat of Campo Mayor of 25 March 1811 was the first Allied victory during Beresford's campaign in Estremadura in the spring of 1811. The town of Campo Mayor had only fallen to the French on 21 March, after an eight day siege, and a small detachment of French troops under General Latour-Maubourg had been left in the town to demolish the fortifications. In total Latour-Maubourg had 2,400 men - 900 cavalry from the 26th Dragoons and the 2nd and 10th Hussars, 1,200 infantry from the 100th Regiment of the Line, half a battery of horse artillery and a force of engineers whose job was to destroy the walls of Campo Mayor and those captured guns felt to be of no use.

The French were entirely unaware of the approach of Marshal Beresford's strong Anglo-Portuguese force, which on 24 March had reached Arronches. On that day the Portuguese cavalry had discovered Latour-Maubourg's outposts, three miles outside Campo Mayor. The French had been sighting forces of Portuguese cavalry on a regular basis since they reached the Badajoz area at the start of 1811, and so did not realize that these horsemen were the scouts of a major army.

On the morning of 25 March Beresford left Arronches, and advanced south east towards Campo Mayor. He split his force into three columns. In the centre, following the main road, was the 2nd Division, with the dragoons in front and Cole's 4th Division behind. Hamilton's Portuguese division with the 13th Light Dragoons and two squadrons of Portuguese cavalry were following a road a little further to the east, while Colborne's brigade and the rest of the Portuguese cavalry followed a ridge to the west.

Three prizes were available to the Allies. The most valuable was Latour-Maubourg's force, one quarter of the French army in Estremadura. Next was the siege train used to capture Campo Mayor and sixteen Portuguese heavy guns, all of which left the town early on the morning of 25 March, almost unguarded, on their way to Badajoz. Finally, if the Allies could capture Campo Mayor before the French could destroy the walls, then the town would be a useful base for further operations. In the end only the third of these prizes would be won.

At around 10.30am the Allied army came into sight from the French outposts. Latour-Maubourg happened to be visiting the outposts at the time, and so was amongst the first to realise that he was facing attack by 18,000 men. He returned to Campo Mayor at high speed, and ordered his force to abandon the town and their baggage, and prepare to retreat back to Badajoz as fast as possible. By the time the first British troops reached the ridges overlooking the town, the French were already on the move, with the dragoons in front, followed by one regiment of the hussars, then the infantry regiment in column of route (long and narrow), and the second hussar regiment to the rear.

If the Allies were to capture Latour-Maubourg's men, then their cavalry would have to hold up the French for long enough for the infantry to arrive on the scene. Wellington had developed a rather low opinion of the British cavalry. He was aware that few of his cavalry commanders had any experience of large scale engagements, and that a single disaster could destroy most of the British cavalry. Beresford had been warned not to risk his cavalry, and he passed that warning onto the General Long, the commander of his 1,500 cavalry. He was given orders to block the line of the French retreat, not to risk an attack against a superior force, but to strike a blow if he got the chance - somewhat contradictory orders that gave Long the leeway to do whatever he wanted.

The British and Portuguese cavalry finally came up on the French column three miles south east of Campo Mayor. The Allied force had split into two during the ride, with De Grey's dragoons to the west, close to the rear of the French column, and the 13th Light Dragoons and the Portuguese horse to the east, level with the French dragoons.

The two sides were very finely balanced. The Allies were outnumbered by the combined French force, but if they could drive off the French cavalry then the infantry would be vulnerable, especially with Allied infantry not far behind. Despite this, Latour-Maubourg decided to offer battle. He formed his infantry into battalion squares along the roads, with the hussars guarding the flanks and the dragoons draw back to the right ready to attack the Allied cavalry if they attacked the infantry.

Long decided to begin by driving off the French dragoons using the 13th Light Dragoons and the Portuguese cavalry. Latour-Maubourg responded by sending his 26th Dragoons to make a pre-emptive attack on the Allied light cavalry. The British 13th Light Dragoons had the best of the resulting melee, driving the French dragoons off the battlefield. Unfortunately for Long, the British cavalry then lived up to its poor reputation, and indulged in a seven mile pursuit of the broken French cavalry, which only ended when the French reached the safety of Badajoz. On their way they chanced across the French artillery convoy, but even that did not stop the headlong charge, and only a couple of the guns were captured.

This left Long with the Heavy Brigade and three squadrons from the 1st Portuguese cavalry to face 1,200 French infantry in squares supported by 500 hussars. His best chance of a decisive victory was gone, but he decided to attack anyway, in the belief that once the French cavalry was driven away, the infantry would surrender. This attack was never launched, for at this point Beresford reached the scene. He was informed that the 13th Light Dragoons were believed to have been lost, and will Wellington's warning not to destroy the cavalry in mind, cancelled the charge of the heavy brigade. Instead, he decided to wait for his nearest infantry column to arrive. Seeing that the British were no longer a direct threat, the French resumed their march towards Badajoz. Beresford trailed behind, waiting for Colborne's brigade to catch up, but by the time the British infantry were coming into range, so were 2,000 French reinforcements from Badajoz under Mortier. Beresford decided to abandon the chase.

The inconclusive results of the combat caused a great deal of controversy in the British army. Beresford and Wellington held that the charge of the 13th Light Dragoons had been wasteful, while Long argued that he had been within a few minutes of winning a conclusive victory when Beresford took command. At the time Beresford and Wellington had the best of the debate - Long was soon removed from command of the Allied cavalry, and Wellington issued a General Order reproving the cavalry for what he saw as a reckless charge. Since then the combat has been seen as a first sign of the indecision that would mark Beresford's time as an independent commander.

The combat of Casa de Salinas of 27 July 1809 was a preliminary action fought on the day before the main fighting at the battle of Talavera. On the morning of 27 July Sherbrooke's and Mackenzie's divisions of Wellesley's army had been posted on the east bank of the Alberche River, to guard the river crossings and make sure that the Spanish army of General Cuesta would be able to cross in safety. Having missed a chance to attack Marshal Victor's 1st Corps in isolation on 23 July, Cuesta had insisted on chasing the French east across the river, only to discover that Victor had been joined by General Sebastiani's 4th Corps and the Royal Reserve of King Joseph. Cuesta had been forced to retreat in some haste, reaching the Alberche on the evening of 26 July. He had then insisted on camping on the east bank of the river, and had only crossed to the west bank on the morning of 27 July. Once the Spanish were across the river, Wellesley withdrew his two divisions, and ordered them to move into their positions on the battlefield he had selected.

Mackenzie's division was ordered to act as a rearguard during this movement. It took up a position around a ruined house, the Casa de Salinas, about a mile west of the Alberche, in an area covered in olive groves. A line of pickets had been placed in front of the division, and Wellesley was using the house as a vantage point, in an attempt to monitor the French progress.

Mackenzie's division contained two brigades. Donkin's Brigade, to the left, contained two battalions of the line (2/87th and 1/88th) and half a battalion of the 5.60th Foot (the rifles). Mackenzie's own brigade, to the right, contained three battalions (2/24th, 2/31st and 1/45th).

Despite these efforts, Lapisse's division of Victor's 1st Corps had managed to cross the Alberche north of the British position without being observed. Having discovered Mackenzie's positions, Lapisse was able to launch a surprise attack on Donkin's Brigade and the left flank of Mackenzie's. The 87th, 88th and 31st Foot were all broken in the first attack, and for a moment the French had punched a hole in the British line.

Luckily for Wellesley, the 45th Foot on the right and the 60th on the left had held their ground, and Wellesley was able to rally the retreating regiments. The British infantry were then able to retreat under fire, until they reached open fields, where Anson's light cavalry were able to come to their aid. Although the French brought up some horse artillery, they were unable to further disrupt Mackenzie's movements, and his division soon took its place in the line.

The fighting around Casa de Salinas was surprisingly costly. The British lost 70 dead, 284 wounded and 93 missing in the skirmish, a total of 447 casualties. Donkin's brigade was hardest hit - it lost 289 of its 1,471 men in the clash, nearly 20% of its total strength. Both brigades would be involved in the fighting at Talavera on the following day, with Mackenzie's brigade suffering 632 casualties, second only to Langwerth's brigade. After two days of fighting, the brigade had suffered 785 casualties, losing one third of its strength.

Combat of Casal Novo

14 March 1811

The combat of Casal Novo of 14 March 1811 was a rearguard action during Masséna's retreat from Portugal that was notable for the reckless behaviour of General Erskine, the temporary commander of the British Light Division.

Having been forced out of his position at Condeixa on 13 March, Ney had taken up a new defensive position at Casal Novo. Marchand's division had a strong position on rising ground, protected by stone walls. When Erskine's men reached Casal Novo on the morning of 14 March the French position was hidden by fog. Erskine himself refused to believe the French were still in the village, and ordered three companies from the 52nd foot to clear away what he believed to be a thin line of French pickets. When the fog lifted it became clear that the five battalions of the Light Division were facing eleven French divisions, and a period of hard fighting followed, in which the British suffered 90 casualties.